The mysterious ancient civilisation that resonates now

Why does the first great Greek civilisation continue to inspire artists and designers today? Beverley D’Silva explores the Hellenistic revival and its roots with the ancient Minoans of Crete.

By Beverley D’Silva

Corinthian columns; sculptures of goddesses and god-like figures; sun-baked buildings bleached bone white; geraniums planted in olive-oil cans; the obligatory cats lolling about – If you’re dreaming of all things Greek, you’re not alone. We’re in the midst of a Hellenistic revival, a fascination with the Ancient Greek aesthetic that’s being most keenly embraced by the post-millennial Gen Z, according to Pinterest. The site reports a rise in trending search terms searches such as Ancient Greek jewellery (up 120%) and wallpaper with an Aphrodite aesthetic (up 180%), and a triple increase in Greek statue art.

More like this:

– What defines cultural appropriation

– Eight nature books to change your life

– How the ‘new naturalists’ live

We can but speculate as to why this should this be, but perhaps there’s truth in the idea that the fantasy and opulence of magical Ancient Greece is highly attractive in a post-lockdown age – just as Dior’s New Look marked a return to indulgent fashion following World War Two’s austerity and utilitarian clothing.

In interiors, fashion and jewellery, the Ancient Greek aesthetic is being embraced (Credit: Mind the Gap Wallpaper)

It’s no surprise that the influence and impact of Ancient Greece resonates today. As defined by Britannica, the phrase refers to the northeastern Mediterranean region in the era between “the end of the Mycenaean civilisation (1200BC) and the death of Alexander the Great (323BC)”, when it was one of the most important places in the world, according to National Geographic. The people of Hellas – as the lands of the Hellenes were called (the names Greece and Greek were conferred on them later by the Romans) were great thinkers, writers, warriors, actors, athletes, artists and politicians.

Roderick Beaton in his history book The Greeks, writes that the Greek civilisations were the “origin of much of the arts, science, politics and law as we know them throughout the developed world today”.

Think Aristotle in his studies of plants, animals and rocks; Herodotus in writing history; Socrates and Plato in philosophy. The Greeks pioneered democracy; reading with an alphabet; the Olympics; geometry and mathematical calculations; health innovations (the Hippocratic oath is still a standard of ethics for physicians); great architecture, like the Parthenon, Temple of Zeus and Acropolis; theatre, care of Greek comedy and tragedy; and language – with an estimated 150,000 English words still in use being derived from Greek words.

All this before we’ve touched on religion and deities. For sheer fantasy value, what can beat the idea of a family of superpowers – such as Zeus, Hera, Aphrodite, Athena, Apollo and Poseidon – dwelling in a cloud palace above Mount Olympus, each controlling a different aspect of life? For some, such as Eric Weiner, author of The Socrates Express, a treatise on the ancients’ philosophy and travel, the Ancient Greeks have a lot to teach us about values today. In an essay on how technology can deceive us, especially in relation to war reporting, he writes: “One way to build a brighter future is by revisiting the past. Ancient Greece in particular.”

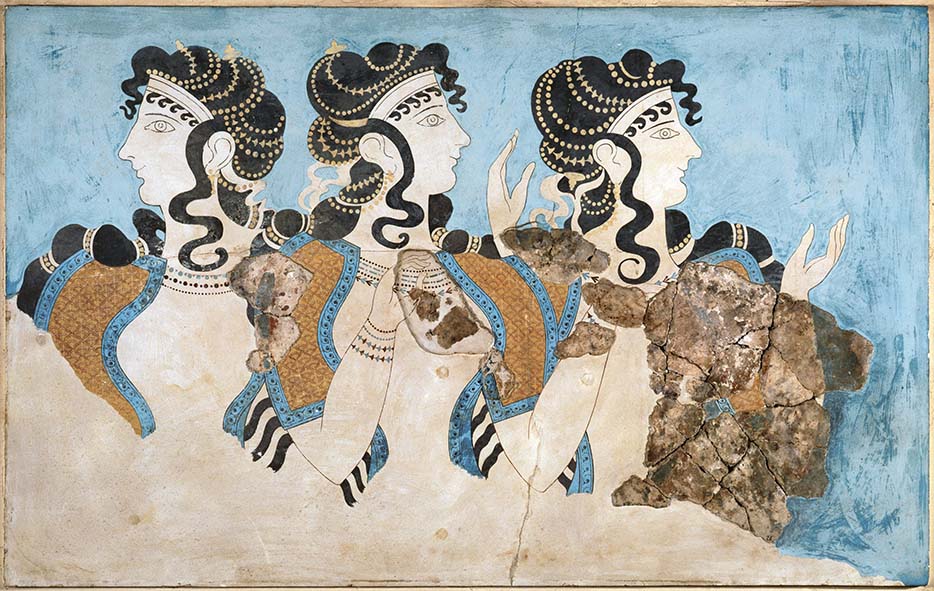

The Minoan frescoes unearthed in 1878 at Knossos on Crete were a stunning archaeological find (Credit: Alamy)

Weiner adds: “The Greeks, imperfect as they were, honoured beauty and justice and moral excellence, and so they cultivated these values. We honour speed and connectivity and portability, so that is what we get.”

The first great Greek civilisation

However if the Ancient Greeks were high-achievers, they stood on the shoulders of giant civilisations that went before them, such as the Mycenaeans, whose story was told by Homer in the epic stories the Illiad and Odyssey. But arguably more fascinating, and certainly more mysterious, are the mighty Minoans. The first great Greek civilisation and the first literate one in Europe, the Minoans dwelt on Crete, the largest and most populated of the Greek islands, from 2200 to 1450BC. They were an “advanced civilisation” that lived in a “land of prosperity and plenty” writes Beaton.

Finds at the ancient city of Knossos revealed a civilisation of highly sophisticated seafarers, who made exquisite jewellery, pottery, sculpture and frescoes

The Minoans came to light when the ancient city of Knossos on Crete was discovered in 1878 by Minos Kalokairinos, a native of the island and an amateur archeologist. It wasn’t excavated until 1900, when the British archeologist Sir Arthur Evans bought the site. He and his team worked for 35 years on five acres of ruins, unveiling the Minoan palace complex, Europe’s oldest city. Finds revealed a civilisation, which Evans named after the island’s King Minos, of highly sophisticated seafarers, who invented advanced drains, porches and verandas to protect them from the elements, and made exquisite jewellery, pottery, sculpture and frescoes painted with animals such as dolphins and bulls.

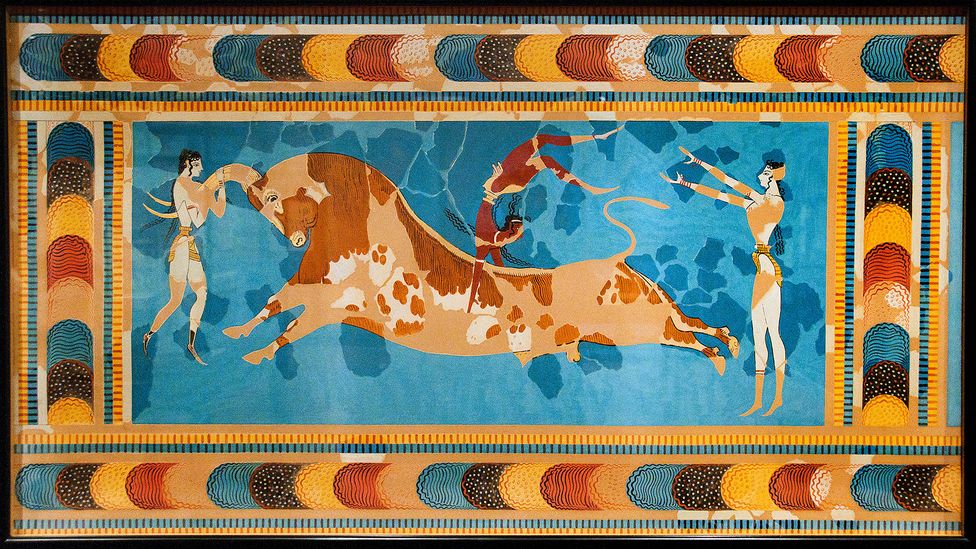

When news of the Minoans hit the press, it drew keen interest from scholars and artists globally. In 1933, the philosopher Georges Bataille and artist André Masson, both French, launched their avant-garde arts magazine, Minotaure. A mythological animal, part-bull, part-man, the minotaur dwelt in a labyrinth designed by Daedalus and his son Icarus, on the command of King Minos; the creature featured in their work, and that of Max Ernst, André Breton, and Pablo Picasso, who made many artworks of it. The minotaur’s physical power and sexual energy, and its links to the unconscious, were aspects Picasso is said to have strongly related to himself.

The remarkably sophisticated art and ceramics created by the Minoan civilisation on Crete still fascinate today (Credit: Getty Images)

Fashion was fascinated by Minoan chic too: in 1912, Spanish fashion and textile designer Mariano Fortuny created a silk scarf titled Knossos, inspired by Ancient Cretan costumes, which made his name. The textiles of fashion designer Yannis Tseklenis, a big international brand, featured ancient Greek vases and Byzantine manuscripts; while Gianni Versace’s bold, Hellenistic designs were a signature style, and became synonymous with 1970s and 80s Greek decadence.

Given the Minoans’ influence on creatives, why do we seem to know less about them than other ancient civilisations? Nicoletta Momigliano, Professor of Aegean Studies at the University of Bristol, tells BBC Culture that one reason is “the Minoan civilisation was relatively circumscribed geographically, being found within the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean regions – so they didn’t have the same geographical spread as the Romans, for example”.

She adds: “Also the Minoans’ systems of writing – Linear A and Cretan Pictographic – have not been fully deciphered, and we do not know much about the languages they used. We have some written documents and can understand some of their content, but not much.” It’s difficult to decipher these texts, she says, because “unless you have something like the Rosetta Stone, you need to have lots of documents, just as when you decipher codes, as they did at Bletchley Park during the Second World War”.

‘Power, beauty and darkness’

But of all the finds at the Knossos ruins, one that caused the biggest sensation was the figures of the snake goddess. Found in 1903, the larger figure has a snake twining around its body and arms; a smaller figure holds snakes in each of her upraised hands. Both have bared breasts and bell-shaped skirts, said to suggest fertility and nature, while the snakes evoke the underworld.

The extraordinary figures of the snake goddess found in the Minoan ruins have inspired artists and designers over the decades (Credit: Getty Images)

According to the Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Crete, where they’re on permanent display, the snake goddesses are “the most important cult objects from the Knossos Temple repositories”. They also beg the question: was ancient Crete a matriarchy? Kelly Macquire, in a podcast for Ancient History Encyclopaedia, says: “Women were prominent in Minoan religion, more than any other civilisation, and we know this because of the snake goddess statues that have been found in Minoan contexts, and the prominence of priestesses in Minoan art”.

Beaton, commenting on Crete’s ancient palaces (of which Knossos was the biggest), writes: “It is possible the greatest deity of them all is the lithe-waisted, bare-breasted goddess often represented on top of a pinnacle of rock, while wild animals or male humans gaze at her in adoration”. It’s unclear whether the island was ruled by women but he adds: “It is a striking fact the Greeks of the classical age reserved prime positions for dominant females in their stories, while largely excluding women from public roles or positions of authority in real life,” he writes, and lists the myths that “are full of powerful, feisty women”, such as Clytemnestra, Electra, Medea, Medusa and Minos’s “insatiable queen Pasiphae”, while adding some had their monstrous sides.

The snake goddess figures have beguiled artists, including US feminist artist Judy Chicago. Her artwork, The Dinner Party (1974-79) is a conceptual piece in the shape of a triangle-shaped table, measuring almost 15 metres on each side, with 39 place settings, each representing a mythical, legendary or historical woman. One of the settings is a homage to the snake goddess, with its table runner embroidered with her name. According to the website of the Brooklyn Museum in New York City, where the work is a long-term installation, the design and colours of the setting’s dinner plate, and that of its cutlery and chalice, are “largely based on the Cretan snake goddesses statues”.

Greek fashion and jewellery designer Sophia Kokosalaki channelled the snake goddess enigma and Minoan culture

In more recent years, fashion designer Mary Katrantzou has infused her work with images of Minoan goddesses, while Greek fashion and jewellery designer Sophia Kokosalaki channelled the snake goddess enigma and Minoan culture more generally. Described by Vogue as “the designer who gave fashion fire and spirit”, Kokosalaki sadly died in October 2019, aged 47. She was born in Athens, and trained at St Martin’s in London, where she built her highly successful luxury brand of clothing and jewellery, always retaining a passion for her home country and Crete, where her parents were born. She said the snake goddess enigma was her “favourite”, since she first saw her at the age six or seven. The goddess, with her “exposed breasts, and tiny waist” represented “power, beauty and also an element of darkness [that] framed my aesthetic early on,” she told British Vogue.

The autumn/winter 2022/2023 Sophia Kokosalaki collection is inspired by the seafaring artefacts associated with Odysseus’s voyage home (Credit: Sophia Kokosalaki)

Kokosalaki’s name as a designer was sealed worldwide with her designs for the opening ceremony costumes for the Greek Olympics in Athens, 2004, and her designs drew high-profile fans such as Keira Knightley and Kate Hudson. Antony Baker, Kokosalaki’s widower and business partner, is now director of the company they founded together in 1999, and has taken on the mantle of designer. Creating the designs himself has been easier than employing a designer, as he tells BBC Culture, “I’m so clear about what she liked… Before Sophia died, she told me she wanted me to keep the brand going, for our daughter, Stelli,” he says.

With the new collection (autumn/winter 2022/23), it’s clear Baker continues his late wife’s vision, and the stunning pieces, wrought in gold, silver and pearls, were recently featured in Vogue. They are inspired by seafaring artefacts like anchors, ropes and the sails of ships, associated with the Trojan War and Odysseus’s voyage home. “I looked into the boat that goes to Hades, and at how the boats were made, and the beautiful associations with that.”

Sharing this passion for all things Cretan is Athens-based Katerina Frentzou, founder of Branding Heritage, a showcase for contemporary Greek designers and artisans, among them traditional weavers on Crete. Branding Heritage’s first exhibition, Contemporary Minoans, showcased how the civilisation’s art, such as geometric and labyrinthine patterns, lotus flower and bee symbols resonate today.

Branding Heritage is devoted to contemporary artisans and designers who are influenced by Ancient Greek heritage (Credit: Lilah Clarke/ Branding Heritage)

Branding Heritage’s collection will launch as a virtual 3D museum in September; among its designs are a necklace by Sophia Kokosalaki featuring silver votive knives; designer Ergon Mykonos’s draped jacket over a gathered skirt with a bra top, trimmed with fabric printed with the snake goddess emblem; and Maria Sigma’s handwoven textiles inspired by the Minotaur and Asterion. Not forgetting a clay vessel decorated with a giant octopus – inspired by a Minoan vessel, the pot is by Lilah Clarke, the granddaughter of Theodore Fyfe, an architect in Arthur Evans’s team, combining ancient culture and modern sensibilities.

Isn’t that, after all, what these artisans and designers are doing today? Channelling a culture because of its beguiling mystery, which it will retain until we find a way to decipher its written texts. Until that day, we can continue to dream and to create, which is perhaps no bad thing. As Einstein famously said: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.”

ORIGINAL ARTICLE here BBC Culture